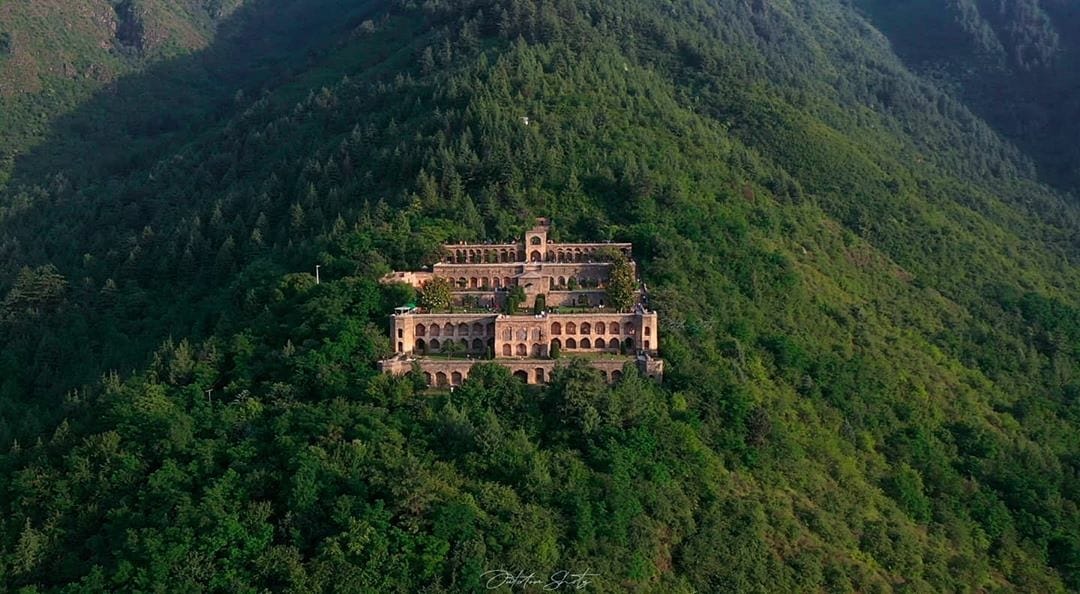

In Srinagar, the Shehr-e-Kashmir, Pari Mahal is a historic monument. Positioned on elevated terraces to the west of Chashma-i-Shahi, it distinguishes itself with breathtaking panoramic views of Srinagar and Dal Lake, setting it apart from other vantage points in the city.

The architectural composition of Pari Mahal integrates elements from both Mughal and Islamic styles, featuring exquisite arched doorways, terraced gardens, and intricate water channels. This fusion of design styles adds to the aesthetic appeal of the site.

The Fairy Tale

Mythology associated with the palace narrates stories of mythical beings and the belief that it served as a place where princesses were purportedly held captive against their will by malevolent magicians. This nomenclature reflects the captivating interplay between reality and folklore, contributing to the allure of Pari Mahal.

“In my childhood visits to the palace, I believed fairies resided there, staying invisible out of fear of humans,” Atirah, a resident said. “I would wear my fairy dress, hoping to be accepted as one of their own. Despite recognising the naivety of those days, the place still holds cherished memories, offering a sense of catharsis.”

En route to the Zabarwan mountain range, Chashma Shahi, (Royal Spring), emerges as a historical garden in Srinagar. Celebrated for its natural spring and Mughal architecture, it stands among the many gardens laid during Kashmir’s Mughal occupation. Positioned just a brief five-minute drive from Chashma Shahi Garden and 11 kilometres from Lal Chowk, Pari Mahal exemplifies the region’s rich historical and architectural heritage.

Mughal Palace

Constructed in the mid-seventeenth century by Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, Pari Mahal served as an observatory for Dara Shikoh’s interests in astrology and Sufism. Functioning as both a library and residence, historical records indicate Dara Shikoh’s stay in the years 1640, 1645, and 1654. The prince met his demise in 1659, executed on the orders of his brother Aurangzeb.

Despite the current state of disrepair, the garden’s original features remain distinguishable. Notably, the Pari Mahal has largely evaded restoration efforts that other Mughal gardens in Kashmir underwent, potentially due to its challenging access.

Architecture

According to architectural historian Sameer Hamdani, a reference to Pari Mahal can be found in Masnavi e Risala e Nisbat, authored by Mullah Shah Badakshi, also known as Malshah in Kashmir. Mullah Shah, a Muslim Sufi originating from Badakhshan (modern Afghanistan) and a spiritual mentor to Dara Shikoh and Princess Jahanara Begum, played a role in their collaborative architectural initiatives in Kashmir.

“Sources indicate that both the prince and his sister, along with Mullah Shah, established an architectural workshop to create Mughal gardens and mosques in Kashmir,” Hamdani explained. “Examples of these architectures still endure, such as the tomb of Dara Shikoh’s wife Nadira Begum in Lahore, the Akhun Mullah Shah Mosque in Srinagar, Kashmir, and the Pari Mahal Garden palace in Srinagar, Kashmir.”

The disuse and secluded location of Pari Mahal in the forest led to fantastical narratives involving fairies and spirits in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. While stories suggest that Dara Shikoh’s wife, Nadira Begum, was also called Pari Begum, there is no concrete evidence supporting this claim, Hamdani emphasised.

An Impressive Spot

Pari Mahal stands out for its integration of architectural elements and its natural surroundings, adding both historical significance and aesthetic allure to the site. Unlike many other gardens in Kashmir, Pari Mahal does not feature cascades, water slides, or falls. While there is a likelihood that fountains once graced the tanks, the primary water conveyance utilised underground earthen pipes, with remnants of open water courses identified.

The garden comprises six terraces, collectively spanning approximately 400 feet. These terraces exhibit varying widths, ranging from 179 to 205 feet. At the topmost terrace, the remnants of two structures are evident: a barahdari facing the lake and a water reservoir constructed against the mountainside.

The reservoir, previously supplied by an overhead spring, is a simple cell constructed with rough stones in lime. It measures 11 feet 3 inches by 5 feet, featuring an anterior with two small arches. An arched drain in the front wall, although partially blocked now, is used to facilitate water flow. Each rim of the terrace wall incorporates a flight of steps leading to the lower portico, measuring 22 feet 3 inches by 4 feet 3 inches.

In the centre of the second terrace, directly in front of the barahdari (pavilion), lies a substantial vessel with brick sides, measuring 39 feet 6 inches by 26 feet 6 inches. The rigid exterior wall is adorned with a series of twenty-one arcs, including two on the side stairs. The arrangement of bends descends in height from the centre, with each arch featuring a niche on top. The height of the niche increases as the arch’s pinnacle decreases.

Notably, the central arch is coated with finely painted plaster, a surface historically favoured for inscribing notices in pen and pencil.

The Terrace

The third terrace emerges as the most captivating segment of the garden from an architectural standpoint. The entrance follows the distinctive Mughal style, featuring arches on both the front and rear sides, leading to a central domed chamber situated in the middle of the east wall. The chamber is embellished with finely painted plaster. Flanking the entrance on either side are several spacious rooms, with the northern room appearing to have functioned as a hammam (bathhouse). Evident remnants of the conduit are notable from the corner of its domed ceiling, making it the most intricately adorned room in Pari Mahal.

On the southern side of the entrance, two other chambers exist, their purpose not easily discernible. In the middle of the arcade, an earthen pipe, initially concealed, is visible. This pipe was employed to convey water from the terrace above, with the water flowing through both an open channel and an underground pipe running parallel to each other. The channel most likely formed a tank in the centre of the main chamber, subsequently draining into the observable remnants of the underground pipe on the barahdari’s surface.

The fourth terrace lacks particularly noteworthy features, except for the remnants of a tank, potentially within a barahdari, extending well beyond the wall’s edge. Along the middle of its north wall, an earthen pipe is discernible, responsible for transporting water to the terrace below.