“Most of us call Budgam chota Punjab (chota Punjab), given its huge vegetable production,” Mehraj-u-Din Nath, vice president of Kashmir Vegetable Dealers Association at Iqbal Sabzi Mandi in Srinagar, told VillageSquare.in. “Farmers of Pulwama, Shopian, Ganderbal, Srinagar, Anantnag, Baramulla, Kupwara and Bandipora districts also contribute significantly to the Valley’s vegetable production.”

According to the statistics at Kashmir’s Department of Agriculture, Budgam district is the largest vegetable producer in Kashmir. During the Kharif or monsoon season, Budgam produces around 175 tons of vegetables, 25% of the 700 tons of vegetables produced in the entire Kashmir region.

The statistics of the agriculture department further reveal that area under vegetable cultivation in Kashmir region has increased from 10,270 hectares (as per a 1981 survey) to 31,250 hectares (2015 survey). There has been a commendable increase in production from about 200,000 tons in 1981 to 800,700 tons in 2015.

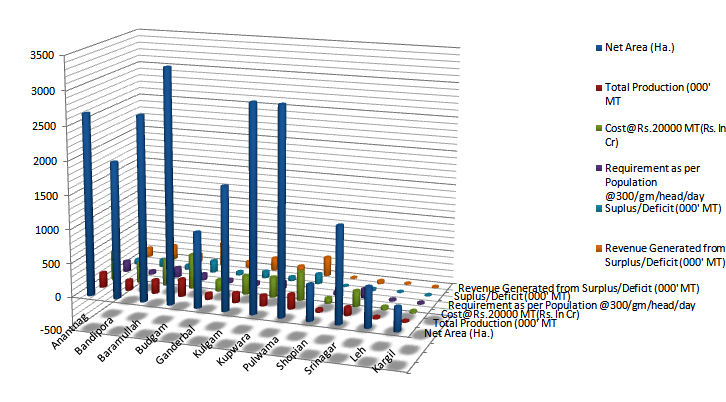

The farmers in the Kashmir Valley as per estimates are exporting vegetables worth Rs 900.00 crore. Vegetable cultivation is being undertaken over a net area of 22,517.96 hectares (gross area of 48,160.92 hectares) with a production of about 1,539.59 (000’MT) with an annual value of Rs 3,079.17 Cr.

The total requirement of vegetables is 900.78 metric tonnes for the population of Kashmir, Leh and Kargil. Deducting daily consumption of vegetable from total production results surplus 638.83 metric tonnes, on which revenue is generated in Rs 1,277.67 Crore.

On the bank of an irrigation stream, an aged-bearded farmer is cleaning carrots. His tribe is either busy in their gardens or selling the produce on the sidewalks. They’re working another day to fuel Bugam’s ‘rising sun’ story—making it Kashmir’s new sunshine enterprise, ‘devoid of any official backing’.

In this small hamlet in Central Kashmir’s Budgam district, the vegetable boom is now inviting researchers’ frequent field trips, and reporters’ growing quest for success stories.

Mindful of this ‘new growth story’ in his backyard, the aged farmer Ghulam Mohammad shifts from carrot cleaning to tend to his vegetable garden.

“Vegetable cultivation isn’t a new phenomenon in Bugam,” the aged farmer set records straight to begin with. “But yes, earlier, it wasn’t happening on such a massive scale.”

Behind the large scale vegetable cultivation were the dried paddy fields.

“All this was paddy land earlier,” says Ghulam, pointing towards swatches of vegetable fields. “But low returns on paddy crop and shortage of water forced the local farmers to give up paddy farming.” Soon as the irrigation facilities were set up, it drove more and more villagers to vegetable farming.

And when the shift took place, Ghulam converted half of his paddy land into Apple orchards and the rest into a vegetable garden. And today, given the sweeping vegetative change over Bugam, he’s quite pleased with his decision.

With the boom, Bugam’s landholders have started employing non-local workforce on the pattern of paddy cultivation and harvesting in the valley. At peace with the transition and evolution, the locals are mulling to engage more workforce in view of the soaring demand.

“Our business is doing great,” says Abdul Quyoom Ganie, a local vegetable cultivator in his mid-forties. “I cultivate vegetables on my own land, besides purchasing vegetables from other farmers and marketing them in different vegetable marts.”

This is now a new trade spinoff for self-sufficient farmers in Bugam. They employ non-locals to till and tender their farms, buy from other farmers and trade it in the bigger markets to ‘make hay while the sun is shining’.

“Each day in our hamlet,” Ganie continues, “farmers send their fresh vegetable stock for different Mandis[vegetable marts] through trucks.” The supply mainly feeds Srinagar’s Parimpora Mandi and Jammu’s Fruit Mandi. “This farming and marketing activity keeps Bugam abuzz and busy for ten months.”

Located in Chadoora, Bugam is around 17 km from Srinagar. The hamlet has already created ‘pockets of prosperity’ in the perspective of economic development through its growing agriculture activities.

But what otherwise looks like a sudden rise of Bugam on the vegetable production front, has in fact been achieved through the silent investment based on toil and slog of farmers over the years.

“Make no mistake about it. Nothing happened here overnight,” says a local shopkeeper Fahreed Shah, who possesses one hectare of vegetable land. “Before coming to age, Bugam saw farmers sweating day in and day out. And the change which we’re right now seeing was inevitable, as more than 80 percent inhabitants of this hamlet are doing it for their living.”

But as the collective and ‘huge’ output was channelized into markets outside Kashmir as exports, Bugam earned a new name: ‘Chota Punjab’. What equally helped this vegetable hamlet to grow was its ability to rise above the traditional forms of farming.

Earlier farmers would use traditional iron buckets to carry water from deep wells with the help of a long wood log, which was tightened on the back side with a heavy stone and the front with a rope. But now, much of that has changed and has been replaced with scientific farming.

“For years now,” says a skinny grower, Mohammad Yaqoob Bhat who owns 25 hectares of land, “Bugam is into production of vegetables. Especially after irrigation facilities were developed, the hamlet boomed more in vegetable farming.”

Around 25 truckloads of vegetables leave Bugam for different markets everyday, Bhat says. Besides that, many traders visit the hamlet to directly buy their bulk stock.

The way Bugam is doing it has already become an inspiration for the larger farming community of Kashmir. The hamlet is leading in vegetable farming in Chadoora and BK Pora belt, as per the latest statistical report of Agriculture Department of Kashmir.

With its net cultivation area of 131.80 hectare, Bugam’s total vegetable production stands at 1,60,533 quintals.

Gulzar Ahmad has been growing vegetables on his land, in addition to the land he took on a lease from his relative, for the last seven years now.

“I earn Rs 15,000 per month on an average,” Gulzar says. “One can earn more in times of high demand and prices.” Presently, as the farmers are busy with cabbage and carrot harvesting in the hamlet, Gulzar says, over fifteen varieties of vegetables are being grown in Bugam.

Despite facing some hitches in the form of infrastructural support and storage, Gulzar and his tribe is now adopting proper marketing channels to bring home more profit. And this is only adding to the ‘sunshine enterprise’ story that Bugam has become on the vegetable front in Kashmir.

Fayaz Ahmad, a farmer in Narkara-Budgam also works as a mason. “But, what I mostly rely on is the assured income from my vegetable farm of two kanals.” He said that he did not find work as a mason always, like in winter for example.

“My land helps me educate my three children, two girls and a son in local private schools,” Ahmad said. “I manage their school fee and other expenses with the money I earn from my vegetable farm.” Ahmad said he earned Rs 100,000 from selling vegetables of his farm.

For Mohammad Yousuf Paul, a 57-year-old farmer in the same village, one cow and a kanal of land, where he grows vegetables, are enough to feed his family of five. “The vegetables and the milk I sell secure me enough money to feed my family,” said Paul. His farm accrued him over Rs 60,000 a year. His half-an-acre of paddy land fulfilled the rice needs of his family.

According to Kousar Parveen, head of vegetable science division at Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology, Kashmir, vegetable cultivation offered farmers about five times more returns than cereal crops.

When their dried paddy fields paved way to vegetable gardens some decades back, none in Budgam’s Bugam village had thought that they would one day emerge as the new vegetable hub in Kashmir. Today as more than 80 percent of the local population is directly engaged with farming, new technology and proper marketing methods are only enhancing the village’s ‘vegetative’ growth.